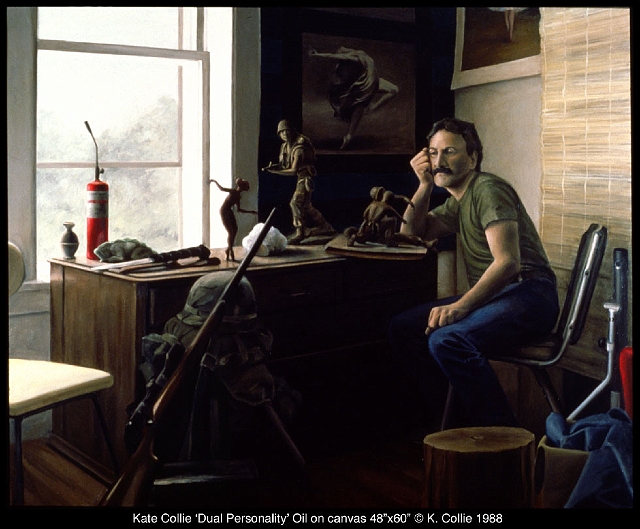

Dual Personality [6 of 7]

'Dual Personality' shows both Steve's soldier self and the artist he became after being treated for PTSD with art therapy.

I was 19 when I went over, I was 19 when I came home and I was two people. I tried immediately to get back into life as I had known it before the war, but I couldn't let the soldier part go. It wouldn't go away. I was retired, but I still responded to sensory input as a combat soldier. I do feel I have two personalities. In combat, what formed after a while was that I had to give up believing I'd survive, just to survive. In doing so, I let rise to the surface a new part of me, a part I never knew existed. That was to live by the senses - smell, sight, sound, touch - to survive. That barbaric or animalistic side, that I think all of us have, became dominant in me while I was in Viet Nam.

Once I took everything military, everything green, everything I had - photographs - that I could find, and I burned it. Still I couldn't forget. I tried to use stop therapy, which is any time a thought occurs to stop it, but I got an ulcer. I had no control over this. I was so maddened by it that I tried to commit suicide. All that did was send me deeper into soldier mode.

What I'm afraid of is someone will upset me by attacking me. My response to that might be the way it was in combat - immediate and lethal. Sometimes this fear in me about hurting other people makes me want to cut my hands off. But they're the same hands that make statues. It's all in the head, it's not in the hands.

-- Steve Piscitelli, May 5, 1987

Excerpts from Massive Trauma and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder: The Survivor Syndrome, by Bruce I. Goderez, MD, staff psychiatrist, VA Medical Center, Northampton, Massachusetts:

Many combat veterans can report a particular traumatic incident which resulted in a sudden discontinuity in psychological functioning, a profound transformation which could occur at different points in their tour depending on the severity of stress and the inherent coping capacity of the individual. This change often came at the moment of the first kill or after seeing a friend blown to pieces. In some cases the transformation was virtually instantaneous, a psychological 'snap' which later may be described as literally having died. In the majority of cases there was a period of hours to days of acute disorganization indistinguishable from the classic description of an acute combat reaction.

The transformed soldier was often hardly recognizable as the adolescent who had prepared for combat a few short months before. All the previous beliefs about the nature of the world and one's placed in it became meaningless. Normal emotions such as love, tenderness, compassion, empathy, and ordinary fear seemed to be gone, having been replaced with the capacity to hate in a totally uninhibited manner which is unimaginable to ordinary people.

The most parsimonious description of this process is that, under the stimulus of overwhelming stress, the original adolescent personality was rather suddenly suppressed or disassociated and replaced by a 'warrior personality' that had been rehearsed in basic training. This warrior personality represents the coherent functioning of an elaborate set of attitudes and skills that favor survival in a combat situation. It is our observation that much of the extreme symptomatology manifesting today represents the persistence into civilian life of various aspects of this warrior personality.